Double Trouble

When we made the decision to relocate to Italy it was not only the arts and beauty that drew us to the ancient country, but also, and perhaps primarily, concern about conditions reigning in the United States. Gun violence and the increasing rancor of American politics seemed to us to have become entrenched in the nation with little hope for improvement during our lifetimes. Although political chaos and even violence in some areas are not unknown in Italy, the small Tuscan town we had chosen for our new home offered a tranquil location in which to spend our later years.

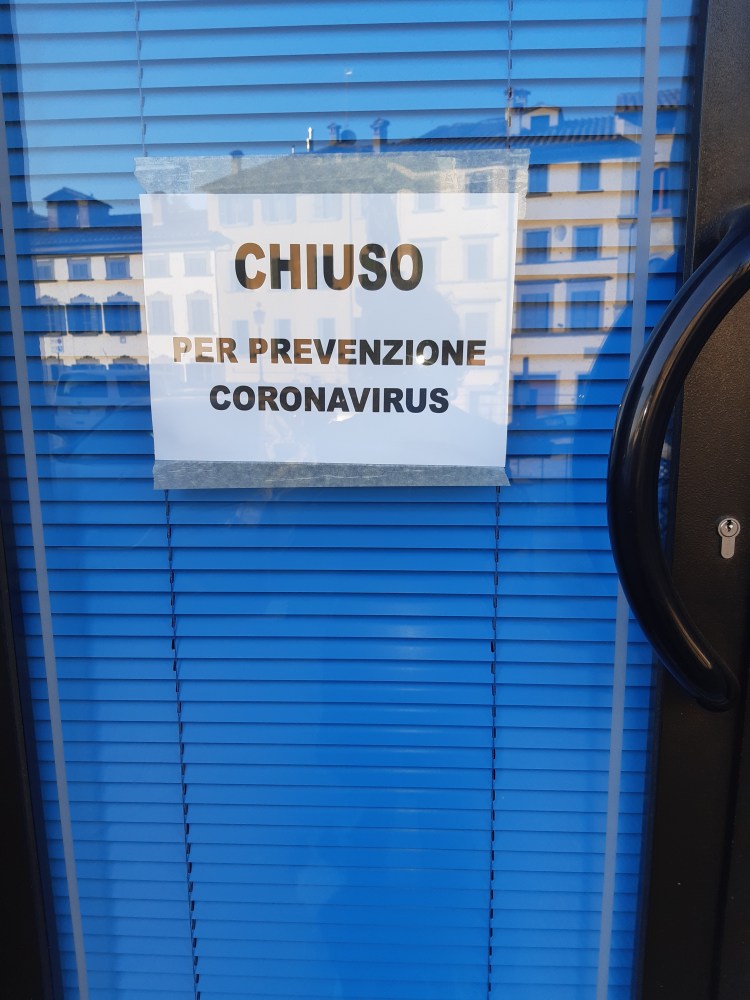

Little did we know that in early spring of 2020 Coronavirus would create a state of emergency in Italy, challenging the country in ways unknown to most of the population. Just before a nationwide lockdown was imposed I met a woman from nearby Monterchi who was an American expat. After we automatically shook hands before remembering we shouldn’t, she said that her eighteen years of living in Italy taught her that Italians were very resilient and that they would survive the pandemic with courage and grace.

As lockdown began we witnessed the truth of her words. First we saw Italians making music on balconies all around Italy, then we saw “Andra Tutto Bene” (Everything will be alright) signs posted everywhere. We watched Premier Giuseppe Conte lead firmly and intelligently as conditions worsened and he had to tell the people of the difficult restrictions that were being set in place. We watched as retired doctors and medical students joined with the health community to meet the challenge of increasing patients in facilities not designed to manage a pandemic. As schools and other institutions closed, we saw museums, libraries and concerts offer videos that took us into spaces no longer open to the public. In our little town residents cooperated from the beginning; staying at home mostly, but wearing masks and gloves and carefully avoiding close proximity when they did go out. In larger cities, where not everyone adhered to the restrictions, we saw penalties imposed, increasingly stringent as time went on and violations, especially among restless young people, began to occur more frequently. Sensitive to the economic impact on working people, the Italian government created funds for the unemployed and established decrees that delayed or ameliorated financial obligations such as rent, taxes or other usual costs of living. It cannot be said that this was a good time to be in Italy, but it was a good time to see how a country might deal with a horrific situation complicated by ever evolving information.

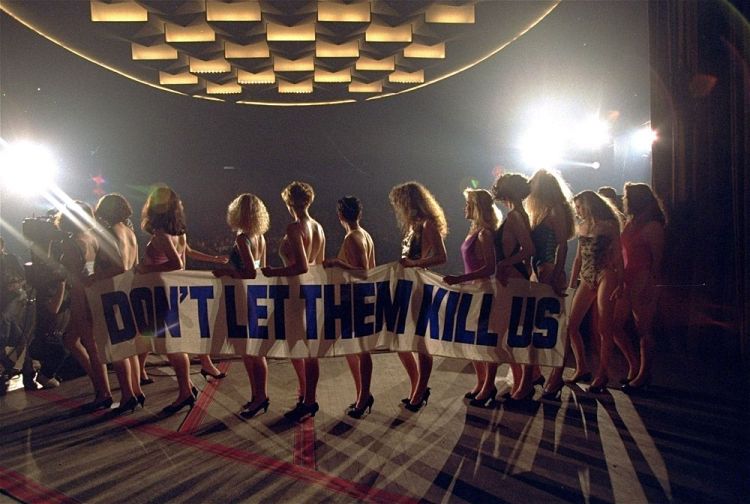

While we were still in Italy the coronavirus took hold across the U S. We watched, appalled, as the lessons of Italy’s experience were ignored and closing of public spaces delayed even as the number of cases increased. We saw reports of men armed with assault weapons storming the capitol in Lansing, Michigan to protest COVID-19 restrictions imposed by the governor. We saw the president downplay the threat of the virus, even calling it a hoax, and offer inappropriate advice for its treatment and prevention. We saw him and other leaders appear in groups without a mask. Particularly in the early phases, the contrast between the sometimes belligerent reaction in America and Italians singing on balconies is stark and seems to sum up the difference in the two nations’ personae.

When we at last were able to fly back to the U S, we came to a state where COVID-19 cases were increasing but restrictions had been loosened so the risk of contracting the virus was significantly greater than in Italy. And as if this were not enough, within days of our return the country was devastated by the brutal murder of George Floyd by policemen and the repercussions that followed. While still in Italy, we had learned through FaceBook and Italian television of the killing of Ahmaud Arbery in Brunswick, Georgia. The two crimes exposed America’s problem with racism in a dramatic and horrible way and Terry and I were both saddened and frustrated as we plunged back into this national blight. As thousands of protesters reacted across America, television broadcast images of mass crowds, sometimes peaceful but often angry and aggressive. And we saw how law enforcement reacted, sometimes with control and even sympathy, but too often themselves angry and aggressive.

This drama begged for a comparison of policing in our native country and our adopted one. America is on the top ten list of the most brutal police forces in the world (Wonderslist; Top Ten Countries With The Worst Police Brutality” by Wardah Hajra). However, Italy too has a reputation for police brutality and has been cited by The European Court of Human Rights for attacks on demonstrators at the 2001 G8 summit in Genoa. A great deal of attention was given to police policy in Italy after the Court’s findings but unfortunately even bringing the matter before the Parliament did not lead to a new Federally mandated standard. Since then there have been a number of cases in Italy of death resulting from beatings of an accused prisoner and while the police officers perpetuating the offenses may be charged and go to trial they tend, as in America, to receive light sentences and even these may be reduced over time. And also, as in America, police may not only be poorly trained, but in general are likely to follow embedded, conservative approaches to crime and criminals. There is, however, no evidence that police brutality in Italy is particularly directed at people of color.

To see Italian police in action check YouTube showing how Italian police deal with crowds of protesters:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2SyxlD8itFA&has_verified=1 and

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3BCW3XmM9hE .

Notice that in both instances the demonstrators approach the police force and it’s not until they are actually in contact that the police react. The demonstrators are throwing stones or smoke bombs before and after the police charge them, contributing to the violence. The Italian police are armed with batons and use them against protesters; in the U S the police are more apt to use tear gas, pepper spray and rubber bullets, which can cause serious injury, to keep the crowds at bay or to clear an area of their presence. An example on YouTube:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nMdcOt1Ow8Y

While demonstrations or protests can be assumed to result from some form of dissatisfaction, Italy does not have a history of long term, systematic suppression of a particular ethnic group so protests do not bring that particular rage to the streets. Graphic videos of murders and other vicious attacks committed by police, or former law enforcement individuals as in the case of Ahmaud Arbery, brought white America to a new and shocked understanding of what black America has long known. This “new” body of evidence is only available because of cameras installed on police cars or videos taken by bystanders–the horrible consequences endured by victims of police brutality in America would have remained unexposed without this footage.

The egregious behavior of American law enforcement has inspired demonstrations not only in America but around the world. In Rome and Florence protest groups gathered on Saturday, June 6 to express their own outrage at what they have seen. Interestingly, Antifa, which has a particular opposition to police, will also stage a protest in Florence that day. The group, often branded by President Trump as terrorist, held another demonstration in Vicenza, Italy on June second. Click below to see a few moments from that event.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uJQUkwWFkkA

It would take an expert to fully analyze all the reasons for differences or similarities in policing in Italy and America and well beyond the scope of my own knowledge. I can only say that the kind of horror we are witnessing now is not something seen in Italy. In spite of the beauty and good will of the city of Hickory, NC our return to the states has been fraught with disturbing events that portray a nation in trouble. Will recent events promulgate the real change that so many hope for? Maybe this time.

And maybe next time we return to the U S from Italy the coronavirus challenge will be better understood and managed and some progress will have been made in the standard of policing. Maybe we will return to a home country more at peace with itself. Maybe the New Normal we speak of will actually have started to be accommodated.