Italy’s most beloved export may be neither olive oil nor wine, but the children’s story “The Adventures of Pinocchio,” the tale of a puppet who wanted to become a real boy. The story is Italy’s third most translated book, published in 260 different languages. The author of this phenomenon was Florentine Italian Carlo Lorenzini (November 1826-October 1890) who wrote under the pen name Carlo Collodi.

After following a career writing political articles for adults, Collodi began to translate French fairy tales into Italian, finding the form that would make him famous. The story of Pinocchio began as a series that appeared in the Giornale per bambini (Journal for children) beginning July 7, 1881. After four bi-monthly publications Collodi concluded the series with Pinocchio’s death by hanging in Chapter fifteen. Collodi’s editor, perhaps appalled on behalf of young followers of the story or maybe just seeking further profits, encouraged Collodi to revive Pinocchio and continue the popular series. Collodi agreed, revealing in the next publication that Pinocchio had been rescued and would go on to many more adventures, becoming the story that we know today.

The version known to most Americans is the Pinocchio of Walt Disney’s 1940 film. Disney artists transformed Pinocchio’s appearance from the early depiction by Enrico Mazzanti (1852-1910).

To this

With Disney’s encouragement, studio artists gave Pinocchio a more fleshed out body and the big eyes characteristic of Disney studio animation to become the Pinocchio so many of us are familiar with today. This more appealing puppet, though destined to suffer from his misguided behaviour, was also not quite the irascible character of Collodi’s version.

In fact, even the piece of wood from which Pinocchio was carved was obstreperous in the original story. The log had been purchased by a Tuscan woodcarver, who intended to make a table leg of it, but as soon as he began to carve the wood it shouted out, “Do not strike me so hard!” and “Oh! Oh! you have hurt me!” Furious at the impertinence of the log, the woodcarver repeatedly banged the piece of wood against the walls to silence it. Exasperated finally, the woodcutter decided this piece of wood presented too many difficulties and offered it to his friend Gepetto for making a puppet.

As Gepetto began to shape the unruly log, he discovered that the two newly carved eyes stared at him with hostility and the nose grew longer with each chip of the chisel. Gepetto cut the nose off repeatedly but it stubbornly grew back each time. As the mouth took form it “derided” and laughed at Gepetto until he begged it to stop at which point the still incomplete puppet sassily thrust out its tongue. Pretending not to notice, Gepetto continued his work, fashioning arms and hands that immediately snatched Gepetto’s wig from his head, and legs that kicked the old carver as soon as they were finished. The patient and hopeful Gepetto, however, forgave all and taking the puppet by the hand showed him how to walk–an unfortunate decision for Pinocchio used his new facility to run out of the house and down the street.

When Gepetto reprimanded the puppet, the local police hauled him off to jail for cruelty, leaving Gepetto to cry out from behind prison bars, “Wretched boy! And to think I have laboured to make him a well-conducted puppet.”

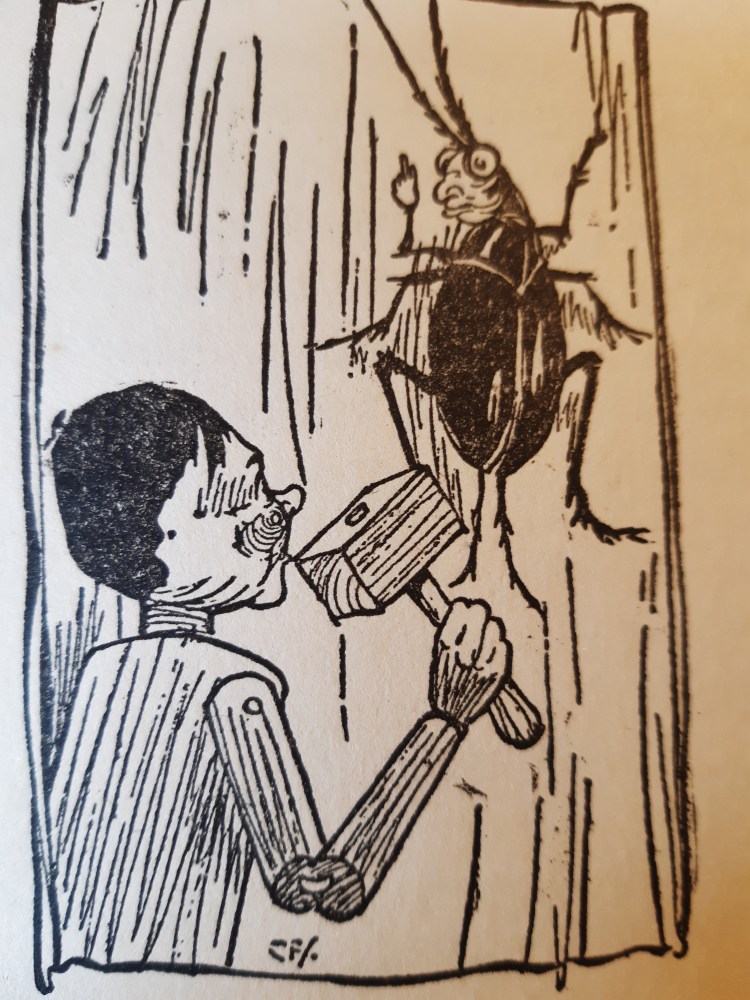

Pinocchio is above all a morality tale intended to direct young readers toward a useful, honest and productive life. Collodi wove a lecture into nearly every chapter touting the virtue of hard work and moral behaviour. Chapter 4 brought forth a hundred year old cricket who scolded Pinocchio for running away saying, “Woe to the boys who rebel against their parents, and run away capriciously from home. They will never come to any good in the world and sooner or later they will repent bitterly.” The wise old cricket then advised him to learn a trade, but Pinocchio responded that his only wish was to “..eat, drink, sleep and amuse myself and to lead a vagabond life from morning to night.” Annoyed by the cricket’s sermons, Pinocchio picked up a hammer and smashed the cricket, leaving it “…dried up and flattened against the wall.”

Disney restored and altered the cricket into the ever present and charming Jiminy Cricket who accompanies and advises Pinocchio throughout the film.

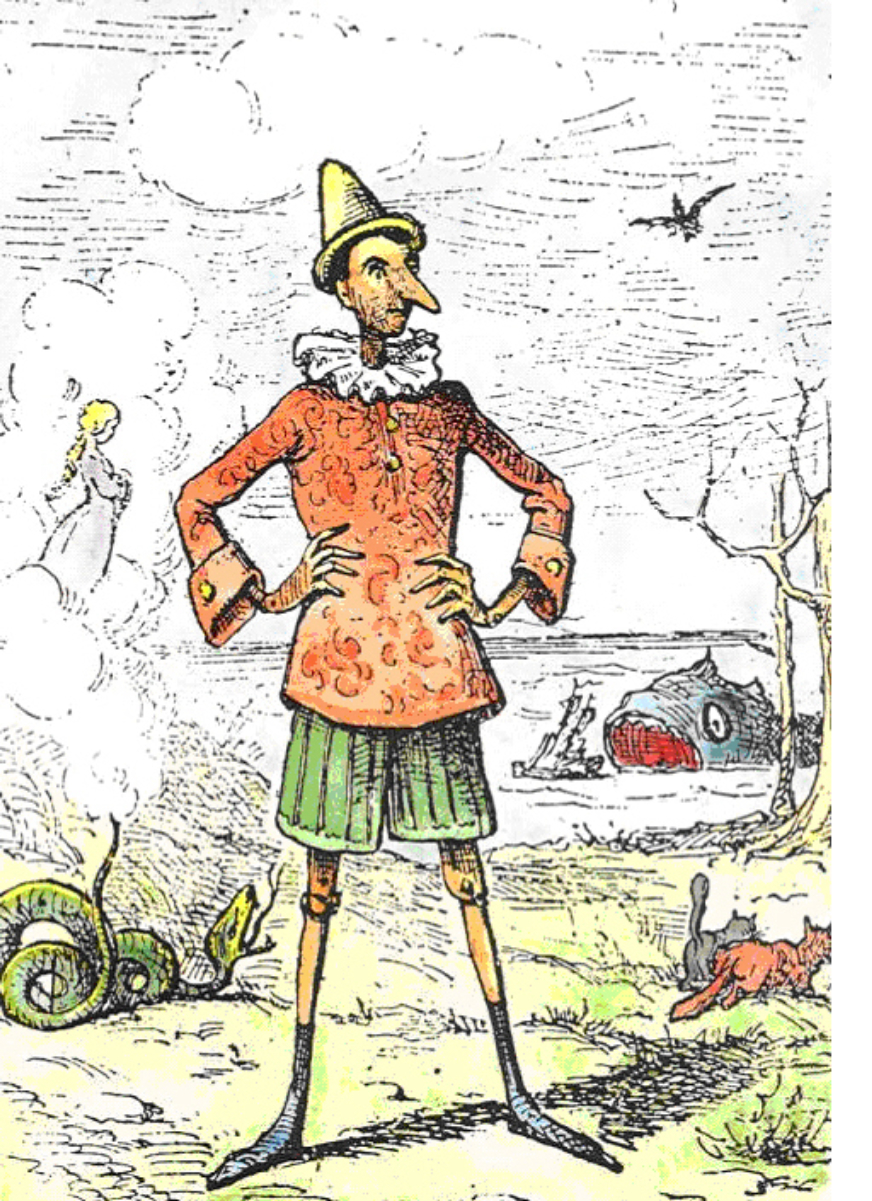

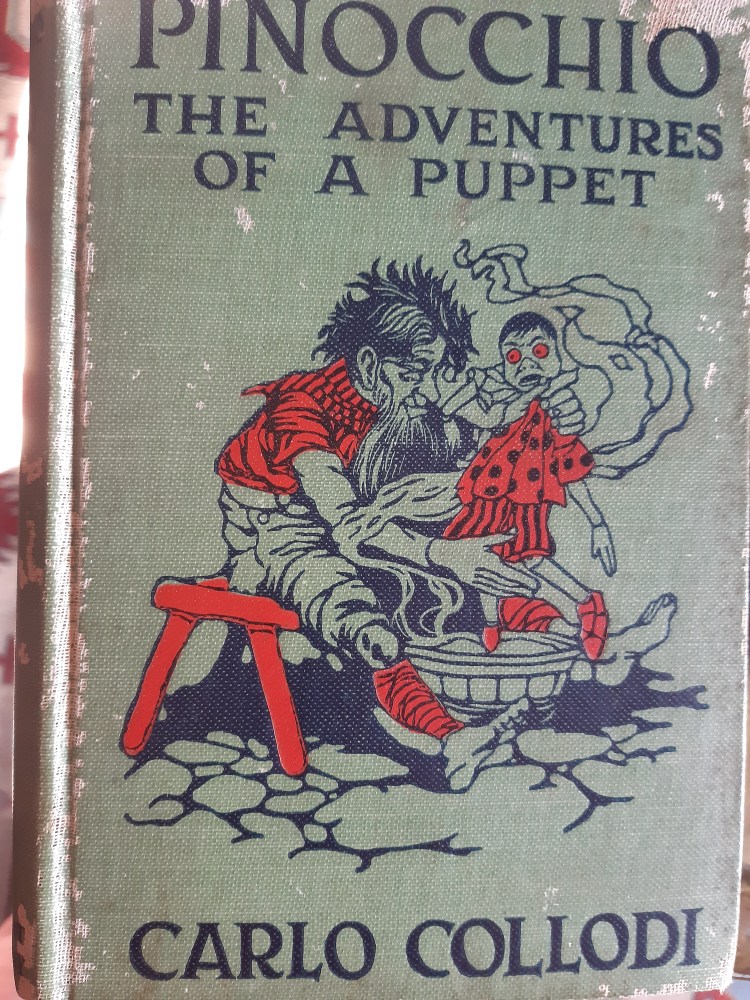

Disney had a genius for transforming old tales into new formats that appealed to more modern audiences. Imagine if the delightful characters of Disney’s Pinocchio looked instead like those seen on the cover of the edition of Pinocchio that I bought, ( A.L Burt Company, New York, 1910?) Trans.M A Murray. Illustrations by Charles Folkard), Pinocchio and Gepetto as rendered by Folkard are grisly, unkempt and look unlikely to either croon “When You Wish Upon a Star” or break into a dance to the accompaniment of music box tunes.

Though Disney’s animated film charmingly recreated the original story, there were still scenes likely to frighten young viewers. The sea monster chasing Gepetto and Pinocchio across a turbulent ocean after their escape from its belly and the scenes of donkeys, once boys, being taken off to become labor animals are both disturbing. Nevertheless, the pretty music and colourful scenes that comprised much of Disney’s film tipped the balance to a promised happy ending and appealed to the taste of later audiences. The film became a major hit that has been re-released numerous times and translated into several languages.

Disney’s film was not the first celluloid production of Pinocchio. As early as 1911 Giulio Antamoro directed “The Adventures of Pinocchio,” a silent film now lost. And in 1936 an animated version was begun by Cortoni Animate Italianiani, Rome, Italy but never finished and now also lost. The image below shows a scene from that film, skilfully rendered even it quite gruesome. (registered to Rauol Verdini and Umbarto Spano).

In time eight more feature films of “The Adventures of Pinocchio” were made in Italy alone plus a number more in countries as diverse as Canada, the USSR, East Germany and the United States. The actor Martin Landau of “Mission Impossible” fame played Gepetto in the U S version of 1996 in an interesting departure from his usual roles. And they still keep coming: Disney is said to be developing a live action version to be released on Netflix in 2022 and a dark version, set in Fascist Italy, seems also to be in the works (directed by Guillermo del Toro and Mark Gustafson).

Not surprisingly, television has offered its own productions beginning in the early 1950’s. Of the 28 or so television broadcasts of Pinocchio, I would most like to see the 1976 version in which Danny Kaye played Gepetto, Sandy Duncan took the role of Pinocchio, and Flip Wilson was cast as the wily fox who convinced Pinocchio to bury his gold coins in a field in order to grow a money tree. There is a DVD available so, who knows, I may get a chance to see it.

Sandy Duncan is the only recognisable person in this promotional photo but Flip Wilson as the Fox is on the left and Danny Kaye, Gepetto, on the right.

Live theater has also staged the popular story in various formats including opera, plays and ballet. “The Other Pinocchio,” written by Vito Constantini, was based on a few sheets of manuscript dated 10\21\1890 and attributed to Carlo Collodi. It is presumed that the manuscript was to be a sequel to the original “The Adventures of Pinocchio.” Playwright Vito Canstantini used these few pages as the basis for his play “The Other Pinocchio” (2000) a work for which he was recognised as an important contributor to children’s literature.

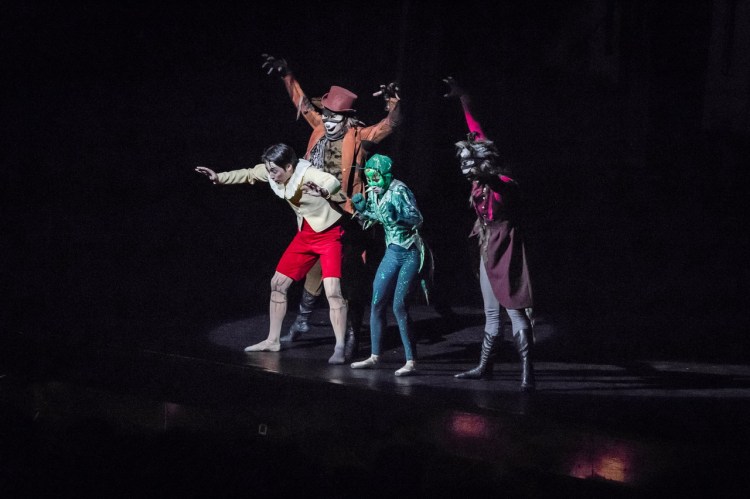

Operatic and dramatic productions of Pinocchio would surely be a treat for any audience as the children’s story migrated to the stage. The scene from a ballet shown below shows how beautifully the Pinocchio story can translate into more classical forms. (Novi Sad, Serbia, Serbian National Ballet, no date given).

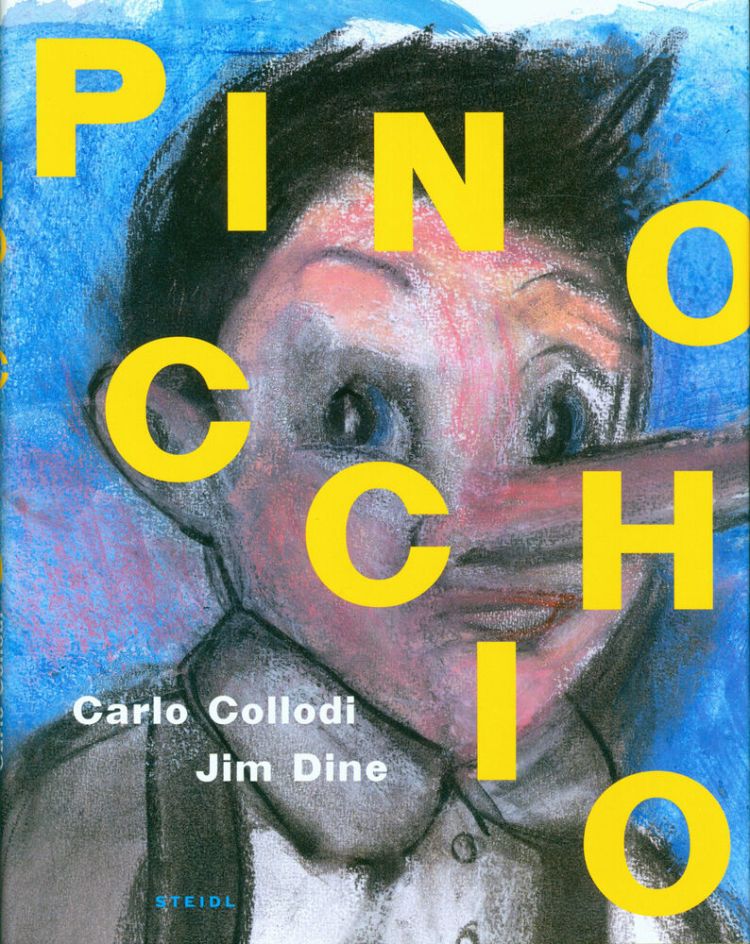

Beyond the world of performance there are a multitude of representations in two and three dimensional form. However, one artist has made his affection for Pinocchio particularly well known as he painted, sculpted and illustrated the puppet across the years–enter Jim Dine, the American artist from Cincinnati, Ohio (b 1938).

Dine saw and was entranced by the Disney Pinocchio as a young child so when in 1964 he saw the puppet lying in a shop where he was buying tools, he purchased it. The figure had a paper machè head and was clothed to cover its articulated limbs. The puppet accompanied Dine through the following years as a sort of accessory to life but in the 1990s Pinocchio began to appear in Dine’s paintings. His Pinocchio paintings and prints have been exhibited in galleries and museums around the world and at the 1997 Venice Biennale.

Dine has also created a number of bronze statues of Pinocchio: “Walking to Boras” located in Boras, Sweden and “Busan Pinocchio” in Busan, South Korea, both 9′ tall. Later he forged the 12′ tall”Pinocchio (Emotional)” installed in front of the Cincinnati Art Museum. To see Pinocchio (Emotional) go to http://www.cincinnatiartmuseum.org

Jim Dine’s “Walking to Boras” in Boras, Sweden. Photo by Stuart Chalmers

Much smaller and able to be held in my hand is Dine’s illustrated book of “The Adventures of Pinocchio” using the Collodi text. I could not resist ordering this from Amazon.it and and now I have two editions of “The Adventures of Pinocchio” to add to our bookshelves.

Who has not known the story of Pinocchio? But I was surprised to learn of the impact of the children’s tale on a range of representations in a variety of media. Why so? And can you imagine Collodi’s reaction to the phenomenon? Who would have thought that a writer of children’s stories would reach such a large, wide-ranging audience across more than a century through a tale originally written for youthful readers of a small Italian newspaper?

Endnote

There is, in fact, a town in Italy called Pinocchio located in the province of Ancona in Northeast Italy. Its name precedes Collodi’s publication. The population there is 3,367 citizens who seem mostly little interested in any connection with a puppet named Pinocchio. An exception is the Pinocchio pizzeria that uses a Disney-like image of the puppet. If you want to see a town celebrating its connection to the puppet that became a boy, you must visit Collodi, the town in which Carlo Collodi’s mother grew up and from which he took his pen name.