Part I: 384 AD to 1920 AD

The ancient town of Anghiari sits on a spur of land elevated between two river valleys, that of the Tiber to our east, and to the west the valley of the Sovara, which runs along the boundary of the town.

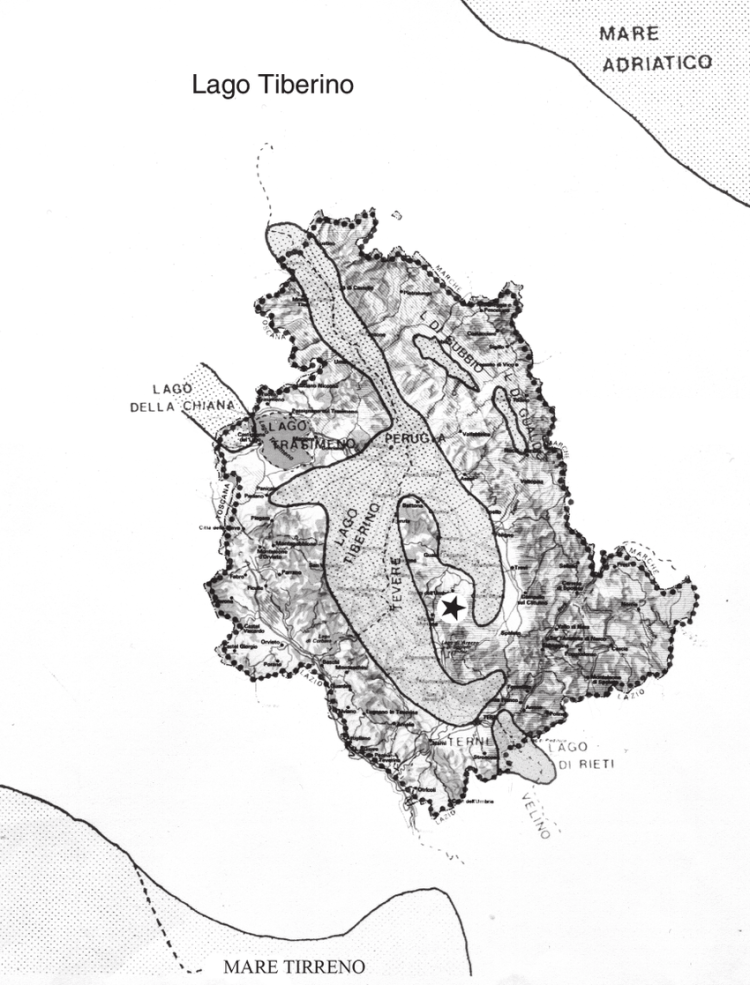

From our little balcony, we look east over the Valtiberina, the Tiber Valley, which today looks like nothing so much as a lake bed. And, as I have discovered, it actually was in times long past. Water, of course, is a feature essential to life and prosperity and any settlement no matter how small relies on the availability of water. Fortunately, for ease of access, Anghiari is also replete with springs which still provide water for the community.

Exactly when the first people decided this piece of land between two rivers was suitable for sustaining life is uncertain, but it is well understood that the pre-Roman Etruscans occupied the area from at least 900 BC. However, the Etruscans, though known through physical evidence, produced only scanty written material and that difficult to interpret. In time, though, the Anghiarese did begin to document the goings on in their village and these records have been preserved in museums and other municipal offices.

From those records we know that Anghiari was established at least by 384 AD when its first named ruler, Barnardo di Lucio, was in power, reigning until 404 AD. Not many years later, 485 AD, Ostrogoth forces moving into Italy attacked Anghiari, gaining another victory in their quest for expanded territory. For the next five hundred years Italy was subjected to invading forces and episodic transitions of power until the Holy Roman firmed its hold on Italy after the Hungarian invasions of the ninth and tenth centuries.

But these are just the major, documented events. Skirmishes with nearby forces happened with some regularity and were destructive even if historical consequences were not as great. The buildings of wood with thatched roofs were easy to burn and destroy with weapons of the time, leaving residents to repair and rebuild after each attack. In an attempt to thwart the periodic invasions, a stone wall was built around the town by the late twelfth century, a precursor to the wall that still surrounds Anghiari.

Shoring up of its defenses was not the only indicator of Anghiari’s move toward a more stable and promising future; in the same period the feudal system was coming to an end and a closer affiliation with the leading city of the area, Arezzo, was developing. This in spite of an earlier (1175) attack by forces from Arezzo destroying the castles of Anghiari. Religious and political institutions were also set in place, imposing greater structure on the social system in which the Anghiarese lived. The village now had Counts and castles and monasteries and monks shaping the lives of the commoners.

In this more orderly environment, citizens of Anghiari and Sansepolcro undertook the challenge to change the course of the Tiber River, bringing it closer to Sansepolcro to give its residents better access to water. In the process, Anghiari gained an additional two miles of flat and no doubt fertile land. Not many years later, (1228) the waters of the Tiber were diverted to form a canal between Anghiari and a nearby hamlet, Citerna, in order to provide water for mills. These are the earliest documented, though hardly the last, efforts to change the course of the Tiber to benefit local populations. Here in the Valtiberina, not far from the Tiber’s source, these and later manipulations have caused the Tiber to behave like a creek meandering gently across the landscape before it becomes the full and swift river coursing through Rome.

Unfortunately, life does not follow a pattern of inevitable progress and 1234 brought to Anghiari and all of Europe “the great cold,” known as the Little Ice Age. The frigid weather not only directly caused the deaths of many Anghiarese but ruined the grape harvest as well, causing a serious downturn in the economy of the region. A lament that “weddings had to be celebrated by water,” is only a sidebar to the hardship suffered, but gives insight to the smaller inconveniences within the disaster. And, as such cycles go, eventually an overabundance of the grape crop caused the price to drop, inciting another economic loss owed to the fickle nature of growing grapes.

In 1385 the Anghiari Vicar, Bartolomeo di Ser Gerello, accompanied by a select committee, petitioned the leaders of Florence for help and support to preserve the often struggling town. An evaluation by Florentine experts determined that the castles of Anghiari were critical to the defense of the area and should be restored. The agreement between Florence and Anghiari included the stipulation that any building constructed after 1310 would be required to be rebuilt of stone and topped with a tile roof. The order not only ameliorated the immediate problems associated with fire and other disasters but produced a built environment that has withstood the ages–Anghiari’s ancient houses still remain centuries after being built.

Across the next half century Anghiari continued to build and to develop institutions that reflected the intellectual and economic benefit of their connection with Florence. But in 1440 the Anghiarese proved their reciprocal value to the Florentine Republic. The Battle of Anghiari, fought between Milanese forces challenging Florence for dominance and Florentine troops protecting their Republic, was waged at the foot of the long hill leading out of Anghiari. The battle remains the predominant point of historical interest for this still very small town and virtually any internet search for Anghiari will mention the Battle.

Fought on June 29, 1440, the battle, according to the writings of Machiavelli, lasted only four hours and resulted in a single casualty when a knight fell off his horse and was trampled. However, Machiavelli wrote that description some hundred years after the battle and his premise has been challenged by a consortium of British and Italian scholars who draw a picture of a much larger event. The Milanese forces arrived outside of Anghiari with 1100 troops and recruited 2000 more from Sansepolcro. In contrast, the combined forces of Florence and Venice were comprised of at least 9000 troops. With their greater power, the Florentines eventually forced the Milanese soldiers into retreat and secured not only Anghiari but the Florentine hegemony. Rather than a single soldier having died, the British historian Michael Mallett postulates 900 troops gave their lives to the fight with more injured or taken prisoner.

The battle is often regarded as only a footnote to history. However, according to Angelo Ascani in his book Anghiari (Citta di Castello 1973), it caused great excitement thoughout Italy, a plausible assertion given the political forces involved and the consequent balance of power. Today the Battle of Anghiari is mostly remembered because of a fresco painting in Palazzo Vecchio in Florence. Leonardo da Vinci was commissioned to commemorate the battle but his fresco began to deteriorate almost immediately and da Vinci abandoned it to take on more promising tasks. Today his work is hidden by a wall built over the fresco. 1

Even in much beleagured Anghiari, where wars small and large, fires, plagues and earthquakes created periodic havoc, new buildings and expanded institutions led Anghiari further along its path to the future. Markets thrived, schools and a hospital were built as was a public wash house and, continually, churches were either newly built or expanded. Roads that had been dirt were laid with brick or stone and the city wall was repaired or rebuilt whenever necessary. A city council headed by a mayor, or Podesta, formed Anghiari’s government, adding a more or less secular structure to the town. In the interest of maintaining good order, it was this body that determined that the harlots of Anghiari, “who were in good numbers,” must reside in one place, and so a brothel was established in the Via Vecchio in 1466. Unsurprisingly given the religious tenor of the times and perhaps to counter the harlot activity, the Virgin Mary appeared before a twelve year old girl in the valley of the Savora River on the eleventh of July 1536 and continued to be seen for the next several days.

As Anghiari’s citizens became more worldly they enjoyed a permanant new theater built in the late sixteenth century and decorated with the works of prominent artists. Villas were built in Anghiari and its environs as prosperous citizens joined the hatters, butchers, pasta makers and other workers who made up the population of the town. Among the new citizens of this increasingly prosperous village was Benedetto Corsi who once lived in nearby Citerna. In 1797 he began to build a palazzo on Anghiari’s main street, tearing down Medieval houses to make way for the Neo-Classical structure.

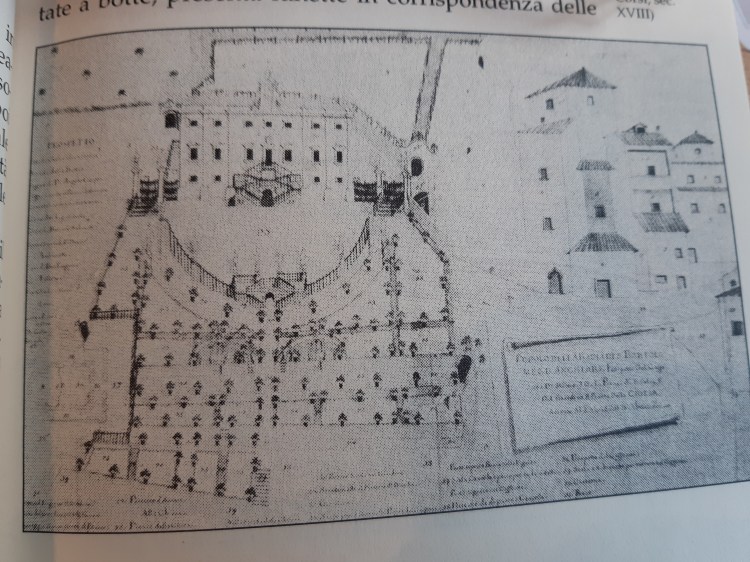

The palazzo extended at the rear to include a large garden, a chapel, theater and coffee house. The slideshow below shows the plan of the Corsi garden and the rear facade of the palazzo, followed by a photograph of the garden in front of the theater and finally, the piazza as it is today.

At the time Benedetto Corsi was building his palazzo, Anghiarese received their first notice that the Italian heritage was under threat. Inspired by, and indeed assisted by, the ideals of the French Revolution, Napoleon led forces to claim territories for what would become the French Empire. Although France had not yet conquered Italy in 1797, soldiers of the French army moved into Anghiari that year. Initially they took over the top floor of a palazzo owned by the Busatti family, merchants who had lived in Anghiari since 1755. In time, the soldiers extended their quarters to include the basement and ulitimately claimed the entire palazzo.2

Unless a personal diary hidden away somewhere describes reaction to the presence of enough soldiers to fill a palazzo, one can only specuate about their affect on the town’s population. In any case, Anghiarese had no choice in the matter and by New Years Eve 1807 were part of the French Empire, celebrating the coronation of Napoleon with fireworks in the main piazza. But, as we know, Napoleon’s reign was relatively short and when he was deposed in 1815 Anghiari reclaimed its Italian roots, and the palazzo was returned to the Busatti family.

Life in Anghiari was not always beset with difficulties; human beings have a habit of seeking entertainment to offset the daily grind and leisure time was plentiful in the past. Not only were there numerous religious holidays, but people didn’t live by the clock as we do now. Anghiarese used to gather in Piazza Baldaccio to play the “Game of the Goose,” a popular pastime with a long history in Italy. Eventually, however, the game was banned from the piazza, leading me to believe it must have been a rough and raucous physical game, possibly dangerous to players or bystanders. Instead I found it was a simple board game appealing to both children and adults, including royalty–a game was once sent as a gift from Francesco de Medici to the King of Spain. Objection to it in Anghiari’s main square may have been based on the gambling it inspired. It is still played today, though not in Piazza Baldaccio, and whether used as a betting opportunity or not it can be purchased online.

Other games enjoyed by residents, male residents that is, were also banned from Piazza Baldaccio and relegated to outlying areas. One of these was Ruzzola a della forme, a game still played in Italy, as is its derivation, Cacio al Fuso, played primarily in Tuscany. In Ruzzola a wheel of cheese weighing from two up to five kilos is thrown by competitors, all vying to see who can reach the greatest distance with the fewest number of throws. The game Cacio al Fusa, played with a smaller cheese wheel, is a bit like Curling with success measured by the ultimate placement of the cheese within a circle.

Another banned game called “Balls, Balls and Bullets,” sounds like a game clearly needing to be removed from the town square in the interest of public safety. A check of the internet did not yield a description or set of rules but I suspect that rather than the violent activity suggested by its name, it was simply a game played, as Bocce and Petanque are, with larger and smaller balls. In both, the larger ball is thrown at the smaller target ball and points determined by proximity to the target. Still, space is needed to play and could be disruptive in a town square. The game was allowed to continue on the road to Fusaiolo, presumably a country road with little traffic.

Not a game but an entertaining tradition, the Scampanata is an event first documented in Anghiari in 1621. Every five years during the month of May, the local Societe della Scampanata meets in Piazza Baldaccio on Thursdays and Sundays at 6:00 a.m. Anyone who doesn’t show up on time is dragged from his home by society members, loaded into a cart decorated with fish and wheeled through the town. Townspeople gather along the streets to jeer the humiliated miscreant and, in the past at least, might throw eggs and flour at him. Originally improvised noisemakers- think pots and pans- added to the din but today it is more likely that a band will follow the cart. This strange custom dates to Roman times when public embarrassment was punishment for those violating the rules or mores of a town and so was a means of maintaining social order. The next Scampanata is scheduled for May of this year (2021).

Of course not everyone is interested in playing competive games or engaging in rowdy community events. By 1830 Anghiarese choosing more sedate entertainment could take a late night stroll in safety under newly installed street lights. A short walk it would have been though for there were only two such lights in the town. And these burned only on nights when there was not a full moon to light the streets. Still, one can imagine that street lighting would have been considered a great boon and a welcome sign of modern times in the village.

With the end of the nineteenth century approaching and the twentieth about to dawn, Anghiari enjoyed a relatively quiet period of continued prosperity and improvement. A new, major street was built connecting the provincial road circling the town to the town center itself. The new road, now named Viale Gramsci, climbs a gentle hill leading to and crossing the area where the Corsi garden had been. In 1887 a gallery was added providing covered access to Anghiari’s major street, Via Garibaldi. (Now Matteotti)

As one passes through the space once occupied by the Corsi garden it would be impossible to miss seeing the former Corsi chapel, dedicated to the family’s patron saint. Purchased by the city of Anghiari in 1900, it later became a votive temple dedicated to soldiers killed while serving in war.

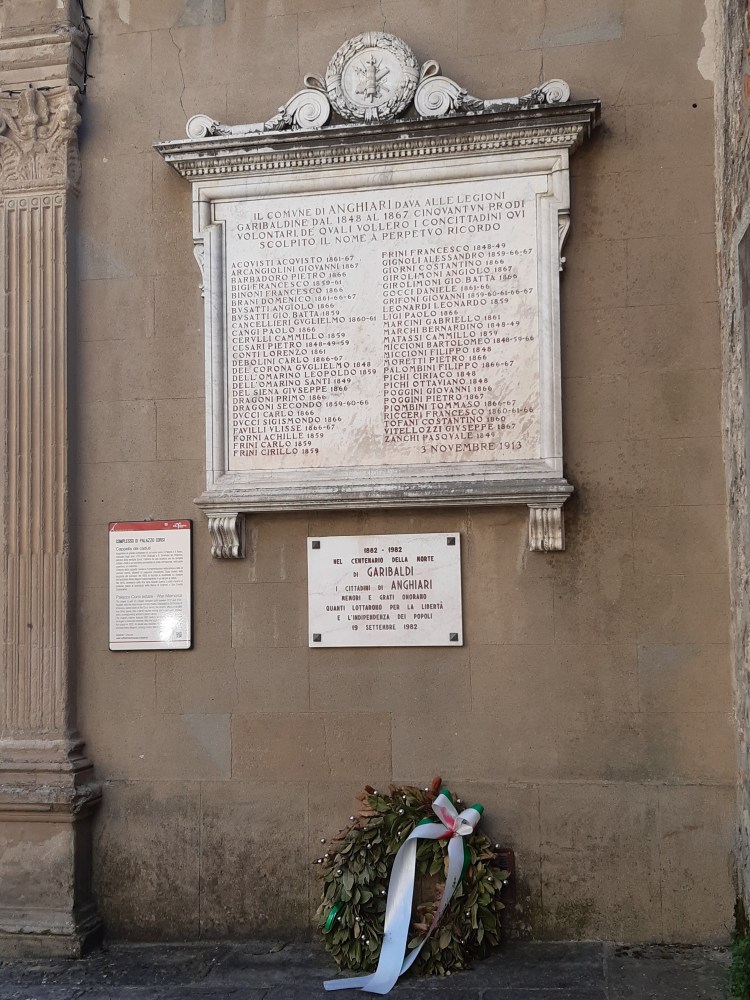

. In 1913 a marble plaque honoring Giuseppe Garibaldi, (1807-1882), Anghiari’s most famous citizen, was installed at the side of the building. Garibaldi was an accomplished and admired military leader, commanding troops not only in Italy but in France and South America. He was even offered a commission by Abraham Lincoln to serve in the Civil War, which Garibaldi turned down. Garibaldi is sometimes referred to as the “Father of Italian Unification” and he did play an essential role. His conquest of southern Italy brought these states under the jurisdiction of the Savoy monarch Victor Emmanuel III, establishing him in 1861 as the first King of Italy.3

In spite of modernization and the benefits it brought to daily life, events of the early twentieth century were about to destroy the tranquillity of the previous years. In the period between 1914 and 1919 both World War I and the great flu pandemic of 1917-1919 appeared in Italy as it did in much of the western world and beyond. In Italy alone, hundreds of thousands died during that time and families in Anghiari would not have been spared. Adding to the misery, an earthquake hit Anghiari in 1917, causing considerable damage in Piazza del Popolo where Anghiari’s government offices are located. A relatively peaceful respite followed these difficult years but war was not finished with Italy yet. And unlike World War I, much of which was fought in northern Italy, World War II came to Tuscany and to Anghiari itself.

End of Part I

***********

Endnotes

1 Leonardo’s lost “Battle of Anghiari” is primarily known through a description by the Florentine artist and historian Giorgio Vasari. There are, in addition, sketches made by da Vinci, a copy of the work painted not long after da Vinci abandoned the project, and a well known painting of the scene by Peter Paul Rubens. No one can actually see da Vinci’s famous work, however, because the ruined painting was soon covered by a second wall onto which Vasari painted his “Battle of Marciono.” In the last 40 years investigation into the possibility of recovering Leonardo’s fresco is in its own right a battle and fascinating story. For further information go to:

2The Busattis arrived in Anghiari in 1755 and set up a general store, selling everything from fabric to food. Across the following centuries the business evolved, responding to economic circumstances, and today occupies a niche market of high end fabrics and linens. Still based in Anghiari, its products are sold across five continents. Visitors to Anghiari can tour the palazzo, once occupied by Napoleon’s forces, to see the original weaving factory with its looms still in place and many visitors cannot resist buying a piece of Busatti goods to take home from their travels. An interview with some of the Busatti family members describing how their business has remained viable for so long can be seen at:

http://www.arezzo24.net/economia/20366-la-busatti-di-anghiari-finisce-sul-financial-times-video.html

I hope you enjoy the interview with these exceptionally nice people who we are lucky enough to have as neighbors.

3Unified Italy of this period was not the Italy we know today. Not only have physical boundaries changed, but its political structure as well. A new, democratic government came about in 1946 after a referendum rejected the monarchy, ultimately leading to the modern Republic of Italy. A full account of Italy’s political history is complicated and beyond the scope of this post.